"That's Progress!" pt. 2

Are we even getting anywhere?

“An all too ordinary story

With an aftertaste so bitter, so bitter

Forced to be someone I don't want to be

I'm losing myself, sinking deeper down

I'm caught in the world wound web.”

- In Flames, Ordinary Story.

In the last entry on this subject, I focused mainly on the specialized pockets and industries and outcomes of progress, technological and otherwise. Now I’d like to fire off some of the bigger guns and discuss the implications of development on human relations and psychology, the AI spectre, and the technology oligopoly, among other things.

The first thing to say is a matter of perspective: we don’t have a choice in participating in progress, one way or the other. This can readily lead the amply paranoid mind to believing that we’re fiddling while ushering in our own doom, happily oblivious due to our constant engineered distractions. Of course, that outlook bears the echoes of the Manchurian consumer fallacy that the critics of mass society of old used to like to massage.

In brief: the view, espoused by organizations like Adbusters and typically trotted out by elements of the far Left, is that globalization and consumer culture were, essentially, an encroaching hegemonic tyranny that we have to stop before it’s too late. The way I see it, if these happening-before-it’s-too-late scenarios bear out over and over without discernible consequence, it’s likely the demographic viewing and interpreting the events that’s the problem rather than the scenario itself.

I will grant that there’s a nugget of truth to it, though. Maybe more so now that we seem to be on the cusp of an Artificial Intelligence (A.I.) revolution. But then, it could also be too soon to tell. Crypto was supposed to be such a revolution that was supposed to give fiat currency a run for its money (pun not intended), and it turned out to basically become somewhere between a novelty and a niche interest because the demand wasn’t there. One way or the other, though, paranoias about coming sweeping changes are as old as the capacity to think itself (refer to the quote from Socrates in my previous entry if you want an example).

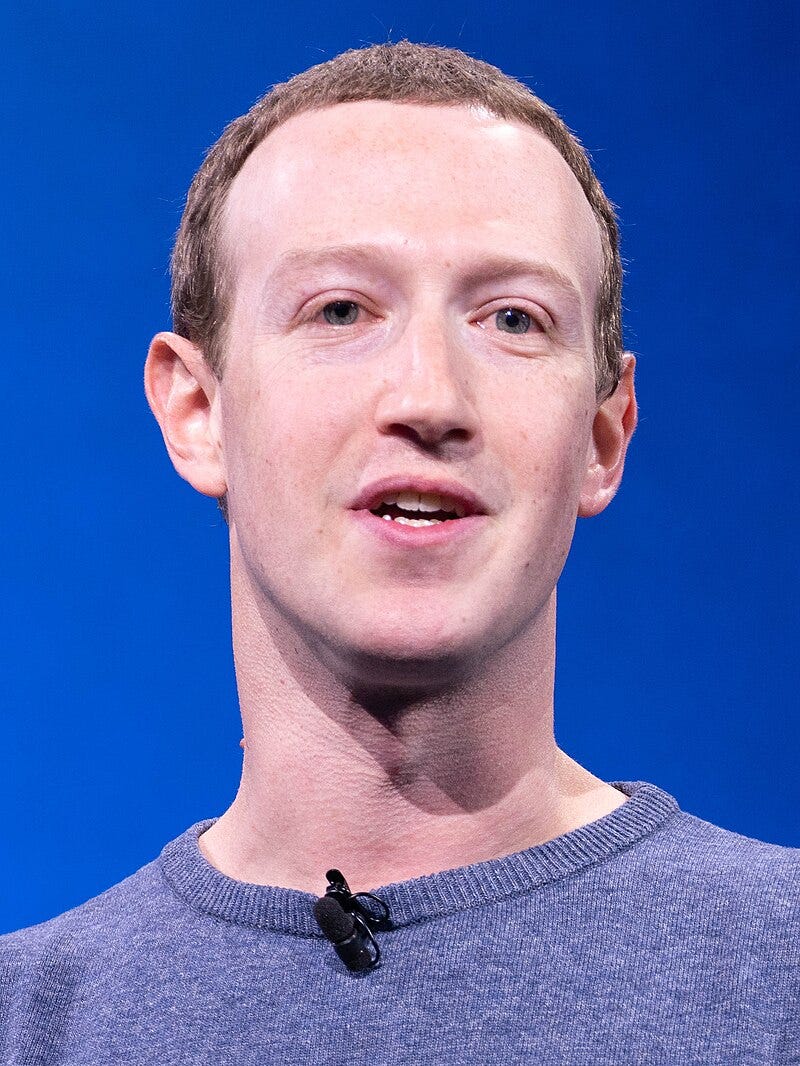

But where the villains used to be government and corporations, now they’re the developers on the leading edge of technology spurred on by competitive and incentive-based ideals. And as these technologies churned out by an essential oligopoly become more necessities than luxuries, we risk sacrificing our liberty in ways we never could to government and advertising (you can’t avoid taxes, but you can choose to ignore the umpteen dozen billboards and pop-ups that inundate your daily vital experience).

AI-AI-Oh!

With some success, I try to separate my two ways of looking at sweeping new developments: subjectively and objectively. The way I figure, if I look at the objective benefits of new developments, it might offset and assuage the chagrin I feel with the access that it grants to the broader public, who I don’t think much of because it seems like the more broadly you grant access, the more prone they become to polluting everything with impunity. Look at how Spain treats tourists if you don’t believe me.

Aggregately, sure: it brings about an increase in productivity. But the issue is that each new development makes it much harder for specialists and the intelligent, because now, all of their access areas and industries are becoming adulterated by those who don’t appreciate them, and who will inevitably bring about a corruption and a demise, as has been noted countless times before.

I don’t share the contention that a rising tide will necessarily lift all boats, because the smaller boats always seem to bear a grudge against the bigger ones, and they think the way to equality (read: for them to have the upper hand) is to now have the ability to fill the bigger boats with weights. That’s how I see A.I. right now.

For all the resistance against A.I., I’m pessimistic. I’ve seen this before. All the resistance against illegal downloading fell through the same way. People fought it, and those who said they would offset it by buying merch and going to shows never followed through. That’s because it’s an example of a collective action problem. In brief, it means that everyone apparently cares enough about an issue, but they believe the other guy cares about it juuuust a little bit more, so they’ll handle it. And what inevitably happens is no one wants to be the other guy because the other guy always ends up thanklessly holding the bag while everyone else freerides.

So we have plenty of precedent to warrant leeriness toward A.I. And one of the impediments to addressing the issues is the widespread doomsaying about A.I. This sort of exaggerated malaise always eclipses a more reasonable concern that could be addressed if people weren’t so busy seriously worrying about Terminators (I’m hoping this is a good example of why I think we should limit access to the public at large; because they harbour contentions like this with a straight face, when they’re not endlessly vindicating against people who they think have an unfair advantage over them because they’re “bourgeois”).

A.I. isn’t like the development of the word processor or other labour-saving devices because of one glaring difference: agency. Word processors are labour-saving devices because they cut down on the labour needed. AI is a labour-hijacking device that people will rest on their laurels (and follies) trusting because, even though people may have concerns about it, people won’t pass up a chance to either be lazy, or to outsource one of their tasks so they can fill their schedule with something else. Remember: people are hard-pressed to want to be the other guy. And the more people there are to freeride off the other guy, the less the other guy wants to bother doing it and the more the other guy wants to give up in futility and frustration.

And this is what makes it better off? All our best minds slowly being whittled down because their resources and patience are being worn thin and the rabble slowly lets the mold of their monoculture grow, abetted by developments constantly being churned out by an oligopoly that seems to have no sense of public duty until they’re dragged before congress (and even then)? There isn’t even any land left to conquer anymore so that our best and brightest who believe in humanity can at least go and start their own self-governed commune.

Silicon Valley Owns Ye All!!!

I liked silicon better when the only time you heard about it was in lewd comments about Pamela Anderson.

With all the talk of government corruption, I think it’s a more pressing priority to keep an eye on corporate oligopoly that we all just give a pass because we owe so much to them. Broadly speaking, humans don’t have a good history of being able to resist temptation simply because they have a duty to sacrifice for the greater good. If they did, they probably wouldn’t be so eager to find ways to outsource all their thinking to algorithms that only perform as keenly as the input from the lowest common denominator, plus whatever biases those who oversee the largely unregulated glut of AI feel fit to program in.

I don’t think that just letting all functions be executed by AI would be such a problem were it not for the spectre of influence from the specialists – the precious few ones – who know how to manipulate it. See, that’s one of the underspoken issues with technological development: as it refines, it creates a larger and larger gap of capability between the casual user and the bitter genius who is still looking to get back at the Stacys who wouldn’t give them the time of day in between writing long-winded manifestos about what gentlemen they are.

Glib though that last comment may be, even if they have totally altruistic intentions, it’s still a problem. When you’re the steward of all your own undertakings, you have a degree of governance. When someone else is, you basically have none. You’re just hoping to God they have the best intentions in mind (and when has that ever gone wrong?) Even syndicated access to broadband technology and algorithms means governance by an oligopoly (or oligarchy, as you may see it) of corporate and specialist figures that you’re blindly trusting. I’m thinking we’re just lucky it hasn’t culminated in a catastrophe thus far.

Truth be told, I think Silicon Valley is a bigger concern than the federal government. On a good day, the government isn’t really affecting your life unless it’s election season and they’re bombarding you with the garden-variety mindrot that is apparently meant to create enmity with your countrymen and believe that the only remedy to the debauchery they’re allowing to happen is by electing another promise-breaking candidate. But anytime we use the internet or a cellphone – which is hours a day – we’re at the whims of those who preside over their production. And unlike government, we have no clue who most of these people are or what their intentions may be. Sleep tight.

How Concerned Should We Be?

“If you ever get close to a human

And human behaviour,

Be ready, be ready to get confused

[…]

There's definitely, definitely, definitely no logic

To human behaviour

But yet so, yet so irresistible…”

- Björk, Human Behaviour.

How concerned should we be? Well, it’s hard to say. Just like any cultural revolution if you’re willing to be honest about it. And if you take a look at the interminable line of failed doomsday prophecies, humans have a terrible track record at predicting the future.

It’s clear that progress – in whatever form it may take – does have ubiquitous downstream effects. In both The Better Angels of Our Nature and Enlightenment Now, Steven Pinker points out using more data than should be necessary that violence and violent crime have declined. On its surface, that’s a good thing. I’m living in a pretty tough neighbourhood where crime used to be pretty prevalent twenty to thirty years ago. As of this writing, I can’t remember the last time I’d heard about breaking and entering around here, and even the drug houses are getting torn down and replaced with new low-rise developments (and dragging up my rent along with the living standards).

Of course, what we don’t get from data is cultural context. On the one hand, perhaps we are ushering in a new form of slowly-burgeoning enlightenment where people are realizing that it isn’t worth it to engage in petty crime, and we could be developing a sort of virulent empathy simply by dint of the tipping point of a practice where we’re not robbing each other because it disgusts us.

On the other hand though, and probably more likely, it’s because we’re getting more docile and satiated. Everyone has a device that’s basically a miracle of modern development that could pacify us from needing illicit gain. But then, that doesn’t happen in a vacuum. It could also mean that people are becoming less sharp because they’re putting their faculties in the employ of every new device that comes down the pike, and that could lead to a different kind of cultural malaise.

In fact, I don’t think it’s untoward to believe that it’s undermining and homogenizing the human need for culture development. I’m not sure that new dances and cultural traditions can arise in an age where we no longer have to get our hands dirty just to entertain each other. In fact, I remember during the great blackout of 2003 when we lost power for two days in the dead of August, it was a time of socializing like none I’d seen before or since. We had no television or radio, and wireless devices were still largely niche. But that was a day when everyone left their houses and got to know everyone on the block. In an environment like that, necessity is the mother of invention. Well, what invention can there be without necessity? Progress, for all its boons, seems to come at that price.

Mind you, I’ll end on a positive note by declaring that I think it’s still a net-positive. These things always have a way of working out in the wash, in spite of the broad naysaying from cultural commentators. Think about how many people you’ve read talking about the lack of fundamentals and laziness of Gen Z. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve seen kids walking around the mall and street with Doors and Nirvana shirts. My seventeen year-old nephew Adam just graduated from firefighter recruitment training, and my other nephews Alex and Ethan think the whole Woke thing is dumb, just like I thought hippies were dumb when I was their age. So it’s not like we all need permission from the corporate-industrial complex to develop values. At least, not yet.